Let’s be honest: most of us are standing ankle-deep in the muddy middle of a massive transition. Institutions are cracking. Economic models are buckling.

Established brands are quaking. Political systems are fraying. Nature is offering up intensely heated feedback. The climate crisis is no longer a looming threat; it’s an ambient condition we’re all living in.

And just as we begin to settle into the new reality, some other future scenario speeds into today and stirs us up even more. Today’s most obvious example of this is generative AI and all the opportunities, questions, challenges, provocations and outright disruptions it invites.

Currently, it’s accelerating into the heart of governance, work, education, commerce, transportation, medicine and identity—writing code, designing social programs, grading students, discovering drugs, drafting legislation—faster and more far reaching than most institutions are capable of responding.

Pull up a chair or leap in?

We’re watching as old frameworks — of trust, social norms, infrastructure, regulation, belonging—splinter under the pressure of what’s next. The tools we built are now outpacing our capacity to steer or brake. Our sensemaking systems and knowhow are lagging behind our technologies. Old rules are lying dead on the hospital bed, but the new ones haven’t yet arrived. And into that gap pours confusion, hope and most loudly, fear.

Whether we like it or not, whether we see it clearly or only feel the tremors, we are at an inflection point in how we live, work, relate, govern, and grow. I’ve been researching and speaking about this for 15 years now—usually behind closed doors with CEOs and senior leaders. When I published The Mesh in 2010, I was tracking early signals of a shift away from ownership and hierarchy, toward access, agility, decentralized platforms and shared value. That book explored how networked systems—built on trust, data, and decentralized participation—might reshape our communities and economies. What I didn’t yet have language for was the deep cultural wobble that would accompany it. That future is here, but it’s landed belly up. Today, the contours of this moment are palpable. They're showing up in our schools, grocery stores, portfolios, inboxes, boardrooms, and townhalls.

This moment doesn’t have a proper name yet. But you can feel it. It’s the creeping silence after you suggest a new idea against the backdrop of the longing to stretch out the familiar. It’s the realization that the systems we were trained to navigate—the maps we inherited—aren’t getting us where we need to go.

This moment doesn’t have a proper name yet. But you can feel it. It’s the creeping silence after you suggest a new idea against the backdrop of the longing to stretch out the familiar. It’s the realization that the systems we were trained to navigate—the maps we inherited—aren’t getting us where we need to go.

What’s the sound of norms collapsing?

I’ve been calling this moment the inflection point between “No More” and “Not Yet”. It’s a frame I’ve been working with for over a decade in private rooms with executive teams, founders, civic leaders. But I’ve come to realize it’s no longer something we can treat as discussion amongst a few or a leisurely nudge. This moment and our growing discomfort with it, is showing up everywhere—in institutions, markets, cities, clubs, schools and supply chains. Provoked in part by, algorithmic bias, sleepless nights, jostled teams, unpredictable infrastructure and weather volatility. It is the cascading collapse of legacy norms.

Do you understand what it takes to lead when the old maps no longer apply and the new ones are a faint sketch?

And if we don’t learn how to stand in it—and move through it—we’ll be led by those who mistake nostalgia for strategy or use our hesitation as their unbridled opportunity.

This is a call to action. To help ourselves and the groups and organizations we rely on or guide. Do you understand what it takes to lead when the old maps no longer apply and the new ones are a faint sketch?

A lesson from Kodak: Fade to black

The world we were trained for—the one we inherited—is dissolving in real time. For most of the 20th century, success was about scale, vertical integration, centralized control. We built systems that were top-down, rigid, and engineered for predictability. Factories, schools, governments, companies—they all followed the same playbook: own the whole stack, reduce variability, control everything.

That model worked, and then until it didn’t.

Take Kodak. They once owned the cows that made the bones that made the agar that made the film. Total vertical integration. But when digital photography emerged and rapidly overtook film,, they couldn’t adapt, despite literally inventing the digital camera. They owned the IP, but they didn’t own the imagination or the courage to leap. They had built an empire of and for value capture. Most processes, people, practices and systems were anchored in repeating the formula that worked. But,

Once innovative, they all but stopped creating. They believed their well-honed success recipe would continue forever.

I saw this firsthand. In the early 2000s, Kodak acquired Ofoto, the digital photo platform I co-founded and helped lead, and an early forerunner to the way we now capture, share and store our lives. Kodak saw the writing on the wall: the digital future was coming. But once inside the Kodak system, our work was quietly suffocated. The company couldn’t integrate what we were building without threatening the enormous margins they religiously pulled from selling film. A culture built to protect legacy cash flow simply couldn’t metabolize the future it had just acquired.

Shortly after the acquisition, I stood in a room with over 300 senior Kodak executives. I asked a simple question: “How many of you consider yourselves innovators?” Only one hand went up.

At another meeting, I was presenting to a group of senior executives. This time, I brought a prop: a suitcase filled with parts — a Brownie camera I’d bought on eBay, a Linksys router box, an old brick cell phone — all duct-taped together. I wheeled it into the room, held it up, and said, “This is the future of photography. If you don’t build it, someone else will.”

As one of their senior executives put it to me afterward, quoting a French proverb: “The sight of the guillotine clarifies the mind.”

By the time they could see the blade, it was already too late.

The room was quiet. They smiled politely. Then, argued. But nobody moved.

Then I reached into my back pocket and pulled out a prototype Nokia had given me — one of their early VGA camera phones. I held it up and said, “And here’s Nokia’s version, coming out in a few months.”

That finally got their attention. The CFO stood up on the table and said to the room: “Give her whatever she wants.”

As one of their senior executives put it to me afterward, quoting a French proverb: “The sight of the guillotine clarifies the mind.”

By the time they could see the blade, it was already too late.

The fate of Ofoto inside Kodak wasn’t a failure of foresight—it was a failure of metabolism. They saw the future. They bought it. And then they choked on it.

Next stop: No more

That wasn’t a personnel issue. It was a cultural one.

These were smart, capable people. But they were operating in an institution that had slowly reoriented itself away from curiosity and toward control—away from invention and toward profit protection. They weren’t there to explore. They were there to extract.

The fate of Ofoto inside Kodak wasn’t a failure of foresight—it was a failure of metabolism. They saw the future. They bought it. And then they choked on it.

That’s the No More: a world where our operating assumptions—our rites of passage, our institutional scaffolding, our inherited biases—are no longer valid. Where did the value go? The map is out of date. And yet we cling, circle the block and pray we can find our way.

The rhythms, assumptions, and incentives that built our worldview no longer fit the reality we’re in. Our institutions—schools, companies, even democracies—are still shaped by those patterns. But the world they were built to serve is gone.

We know what’s ending. But what’s emerging is harder to name.

Not Yet

If we squint, we can see the outlines of a new world—what I call the Not Yet. It’s emerging in strange places: in networks, in experiments, in decentralized ecosystems that move fast and learn faster. This is a world of porous boundaries and lightweight infrastructure.

Think of culture as the API that allows for this—a permeable interface between your core values and the outside world. Like a well-designed API, it lets in signals, challenges, and collaborators without abandoning what makes you you. It’s not about absorbing everything or staying sealed off; it’s about defining the rules of engagement so the system can learn, adapt, and remain coherent.

One of my favorite books is Tristan Gooley’s How to Read Water. In it, he writes about how river pilots accept that they cannot control the power or flow of the water, or where the rocks lay in front of them. Their mastery requires both respect and intimacy — reading the way forward means careful watching of everything that shifts. That requires agility, not rigidity. It demands curiosity over certainty. It calls for sensors to announce critical insights that guide our regeneration. Change is accelerating relentlessly, and that’s not going to let up., In this inevitable reality, we all must become learning engines, or immerse ourselves in the kinds of networks and communities that function as such an engine collectively. This is important work to be done. In your world, think about who you would invite into this work – people to talk, read and think together with. In your collective space, work or otherwise, if this work isn’t already happening, as yourself if you can be the initiator.

The “Not Yet” is where innovation lives. Where small, scrappy teams (and communities) build, test, discard, and try again. Where friction isn’t failure—it’s feedback. It’s also where people feel most vulnerable, because it requires admitting: “I don’t know what happens next.”

And that’s not only okay, it’s essential. To succeed in this moment we are open, searching, listening and learning. It’s better to be curious than afraid.

Mapping the Inflection Point

I often use a lifecycle model derived from the work of Ichak Adizes to help frame where we are in this transition. Every company, every institution, every culture—even every idea—moves through phases: birth, infancy, adolescence, stability, aristocracy, bureaucracy, and eventually, death.

- Birth — sparked by a question

- Infancy — testing identity and market

- Adolescence — early validation, early chaos

- Stability — it works

- Aristocracy — dominance through habit

- Bureaucracy — control ossifies

- Death — slow fade, then gone

Crucially, the point of stability is also a fulcrum. To the left, we have value creation. To the right, value capture. Most companies I work with spend their energy on capture: squeezing more juice from old fruit. The Not Yet is on the left. The No More, on the right.

The challenge for those of figuring out how to lead through it is to balance both. To build a portfolio of capabilities: some that pay the bills, others that build the bridge to what’s coming. That requires courage, because the Not Yet is messy and the ROI is fuzzy. But the cost of standing still is death by relevance starvation.

Here’s the catch: you can’t just bolt on innovation. You need a culture that stops what isn’t working (RIP, Google Glass), and the guts to put people in rooms where they’re not afraid to raise their hands and say, “I’m here to invent.”

Signals from the Edge: Lessons in the Not Yet

Different players are responding to the No More / Not Yet moment in very different ways.

Airbnb didn’t invent hospitality, but they reimagined its infrastructure. Instead of owning the buildings, they built trust systems, data engines, and dynamic pricing models that allowed them to scale faster and more flexibly than legacy hotel chains ever could. In under 20 years, Airbnb’s market cap eclipsed that of the biggest global hotel chains—without owning a single property.

Meanwhile, Google, at its best, built an ecosystem designed for adjacent bets. From acquisitions like YouTube, Waze, and Kaggle to experiments via Google X and Google Ventures, they’ve continued to invest in new frontiers even while defending their core ad/search aristocracy.

And now we’re seeing signals of a different kind of response emerging — smaller, more specialized, more culturally attuned to what the Not Yet demands.

This year, the French AI company Mistral launched Magistral, Europe’s first AI reasoning model — deliberately designed to prioritize transparency, auditability, and domain expertise over sheer speed or scale. In contrast to the American and Chinese giants, Mistral is leaning into its EU roots: creating an AI platform that supports traceable, compliant reasoning for high-stakes contexts like law, finance, and healthcare.

It’s too soon to know if the EU will catch up to the U.S. and China on AI dominance — but that’s not really the point. Players like Mistral signal the kinds of decentralization and diversification we’ll need if we want the Not Yet to be more inclusive and accountable than the No More.

Today’s intersections are data-rich and people-dense. We’re sensors with legs, streaming constant signals about our needs, preferences, and connections. The organizations that thrive are the ones that treat data not as exhaust, but as learning.

But here’s the catch: you can’t just bolt on innovation. You need a culture that stops what isn’t working (RIP, Google Glass), and the guts to put people in rooms where they’re not afraid to raise their hands and say, “I’m here to invent.”

Intersections and Collisions

The systems we built in the 20th century were optimized for monoculture. But monoculture is fragile. Just ask anyone trying to grow grapes or run a legacy media company. In contrast, diverse systems—ecologically or economically—are resilient. They bend, adapt, and surprise. They contain multitudes.

That’s why I spend so much time thinking about intersections. In cities, intersections are where 80% of the collisions happen—but they’re also where the energy is. Different people, ideas, cultures, and business models slam into each other and sometimes, magic happens. Sometimes, tragedy. But always: potential.

Today’s intersections are data-rich and people-dense. We're sensors with legs, streaming constant signals about our needs, preferences, and connections. The organizations that thrive are the ones that treat data not as exhaust, but as learninginput. Not just something to mine, but something to respond to.

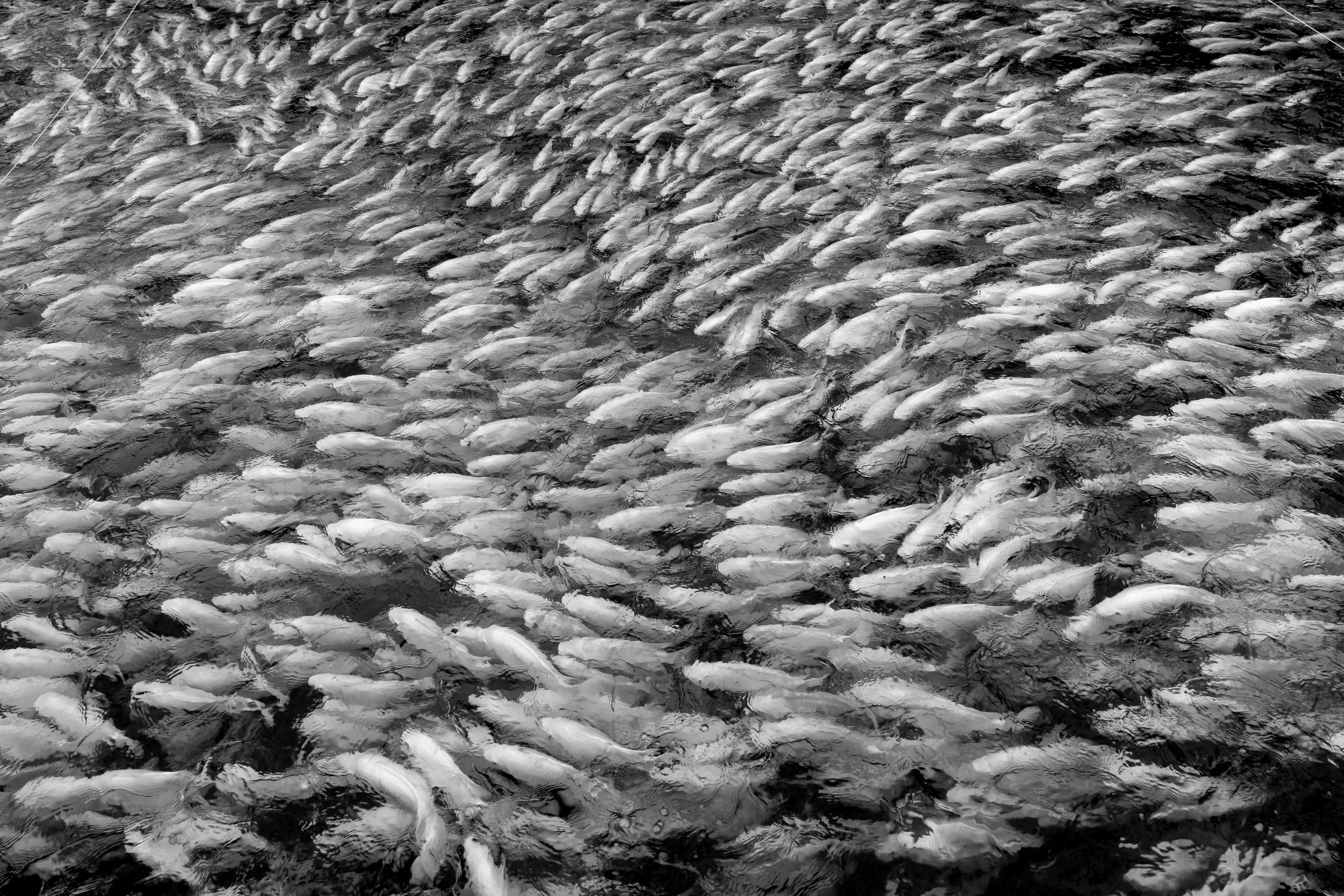

Don’t Be a Whale in a School of Fish

Let’s talk about power. In the 20th century, we were trained to be whales—massive, slow-moving, centralized, dominant. In the 21st, power has shifted to the school of fish: agile, decentralized, coordinated in real time.

Network effects change the game. Whether it’s Airbnb, neighborhood gardens, open-source software, or generative AI, systems that grow through participation and sharing will always outpace those built to hoard and defend.

But here’s the hard part: most leaders are still playing tennis on a lacrosse field. They haven’t adjusted the rules, the tools, or the rhythm. They think their competitors are the other dinosaurs when in fact, they’re being stalked by new creatures who aren’t even in their lexicon.

The challenge isn’t only to be optimize for speed. It’s to think differently about what value is, how it’s created, and who gets to play.

When the Old Order Bites Back

It would be a mistake to treat the No More / Not Yet frame as merely economic or organizational. These shifts aren’t just reshaping businesses—they’re destabilizing whole societies. And wherever systems are in transition, fear is never far behind.

We see it in the return of strongman politics, the global erosion of democratic norms, and the weaponization of nostalgia in public discourse. We see it in the way climate adaptation plans stall while extraction accelerates. And we see it in how governments and institutions respond to the rise of generative AI—not with foresight, but with panic, spectacle, or paralysis.

The speed of the tools has outstripped the speed of our ethics. The infrastructures we’ve spent decades building for deliberation, inclusion, and accountability weren’t designed for this level of acceleration—or ambiguity. So instead of adapting, many double down on control.

Fear becomes strategy by default.

There’s a visceral panic that comes from being visibly outpaced in a system that’s evolving beyond your skills, your stories, your language. And when people are told—explicitly or implicitly—that they no longer belong, they find someone who will say they do.

What we’re watching isn’t just a resurgence of authoritarianism—it’s a reaction to perceived irrelevance. People who feel locked out of the Not Yet don’t go quietly. When you don’t understand the rules of the new game, and you don’t trust the referees, burning down the field starts to look like a kind of logic.

There’s a visceral panic that comes from being visibly outpaced in a system that’s evolving beyond your skills, your stories, your language. And when people are told—explicitly or implicitly—that they no longer belong, they find someone who will say they do. Someone who offers the comfort of old hierarchies and even older enemies.

This is what fear does. It invites us to retreat into the No More, even as it collapses beneath our feet. It dresses up resistance to change as moral clarity. It rewards performance over participation. It makes regression look like protection.

This backlash isn’t the new world. It’s the turbulence of transition. Authoritarianism may feel ascendant, even permanent. But it’s not the Not Yet. It’s the No More refusing to go quietly.

We’ve seen this play out before: in corporate culture, in urban planning, in immigration policy, in climate denial, in educational backlash. And now, as AI reshapes how we work, decide, and govern, we’re watching the same script run again: retreat, control, blame, stall.

But this is not a revival. It’s rigor mortis.

Even now—especially now—it’s important to remember: this backlash isn’t the new world. It’s the turbulence of transition. Authoritarianism may feel ascendant, even permanent. But it’s not the Not Yet. It’s the No More refusing to go quietly. (Like a B horror movie, the monster seems dead, but isn’t.) The fear, rigidity, and doubling-down we’re witnessing are not signs of a fixed and brutal future—they’re symptoms of a system in decay. What we’re living through isn’t a landing. It’s a wobble.

Some have argued that this backlash is fueled not just by too much change, but by too little: a sense of cultural and aesthetic stagnation that leaves people hungry for drama, any drama, even if it’s destructive. When nothing seems to move, even a wrecking ball looks like progress.

If we want to build futures that include more people, not fewer—if we want to avoid letting fear set the terms—we need to treat these reactions not just as political crises, but as design failures. Failures of invitation. Failures of imagination. Failures of infrastructure.

Because when people aren’t invited into the Not Yet, they don’t just opt out.

They fight back.

So, what do we do?

It was the Clash’s Joe Strummer that immortalized the line “The future is unwritten.” It’s one of those things that seems obvious once it’s said, but it takes somebody to say it. So, what’s the line that comes after?

This isn’t just a personal leadership challenge—it’s a networked one. We need tools and relationships that distribute agency, not just concentrate it.

We don’t get to control the timeline. The Not Yet will come, with or without our consent. The question is whether we’ll have a hand in shaping it—or be shaped by those who are willing to destroy more than they build, just to feel in control again.

We can’t meet this moment with timid tweaks. We need to build organizations, cultures, and coalitions that are unapologetically experimental, conspicuously curious, and structurally inclusive. We need new rites of passage, new trust systems, and new voices at the table.

That leap doesn’t require knowing exactly where we’ll land. It requires being conspicuously curious. It requires saying, and creating the space for others to say: I honestly don’t know, and I’m excited to find out.

That’s not just a job for the people in hoodies or holding venture checks. It’s on everyone. This isn’t just a personal leadership challenge—it’s a networked one. We need tools and relationships that distribute agency, not just concentrate it.

In the next article in this series, I’ll dive deeper on what it takes to build a culture for the Not Yet, and in particular how we can use specific tools and canvasses to map this all out and make it all a bit clearer.

Meantime, if you lead—anything, anyone, anywhere—start by asking yourself:

- Are we creating or merely capturing value?

- Do I act to build or to protect?

- Do we inspire curiosity or punish it?

- Are we waiting for the uncertainty to ebb before pushing ourselves to act and learn by doing?

Better to build the future, than be haunted by the past.

This is the work of leadership now—not commanding, but reading the water and sticking at least one paddle in the turbulent current..

Welcome to the messy middle. Jump in! Let’s make a better Not Yet.